My Bondi (story blog/non-fiction)

- By Robin Barker

- •

- 13 Jan, 2017

But don't be misled. Bondi surf can be wild, rips can be treacherous, undercurrents strong enough to knock you off your feet. Charmingly unpredictable, it can also be a mellow, barely-ruffled pond, an orderly succession of rising and falling breakers, a lumpy medley of foam and chop and everything else in between.

Behind the beach lies the suburb, historically much of it a suburb of treeless streets, small cottages and rundown blocks of flats, sun-baked bitumen and singed grass. The surrounding hills and mighty sandstone cliffs with sweeping views of the magnificent coastline were largely taken over by the wealthy. Their walled-in designer homes, extravagant showpieces of ambition and prosperity, have become grander and grander over the decades even as the beloved beach below has remained a classless wonder open to all.

Bondi is not, as many overseas visitors anticipate, a pristine stretch of beach on a lonely coastline populated by birds and kangaroos. It is a noisy, somewhat polluted inner city suburb with pockets of ugliness that takes newcomers by surprise. Tourists discovering a crowded urban beach-front instead of a remote paradise are inclined to describe their trip to the famous Bondi Beach as one big let-down.

*

Once, several decades ago, New Years Eve revellers covered our beautiful beach

in a glittering mass of glass, tin and plastic so closely packed not a grain of

sand was visible. Around the same period ocean pollution made the wading pool

at the north end such a serious health hazard parents were advised to keep

their kiddies away. Out in the ocean it wasn't uncommon for swimmers and

surfers to come face to face with bobbing turds. Or, in the local lingo, Bondi

cigars.

Thankfully those days have passed. Now, thanks to the construction of deep sewage outfalls twenty-five years ago, a pristine turd-less surf crashes and curls into the creamy sand, syringes and needles have mostly disappeared, grog and fags are banned on the beach and shady trees divide the main drag and line the streets

All of which is to be applauded, however there is a fine line between cleaning things up and preserving the best of the old free-wheeling, egalitarian, grungy mix of buildings and the idiosyncratic blend of working class, middle class and migrant communities Bondi has been famous for. Bogans, artists, tradies, elites, socialists, capitalists, greenies, small business owners, Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, agnostics, atheists, the near-naked and the covered-up, and currently a prime minister, all rub shoulders at Bondi.

Naturally everyone wants to swim in clean water and walk on friendly sand but in attempts to turn Bondi into a groomed showpiece of tolerance and good taste there’s been a tendency to overdo the grooming.

Thankfully, Bondi, even in the grip of unrelenting gentrification, defiantly keeps resisting makeover efforts. The grungy look is still around many streets and, despite the trees and pot plants and outdoor cafes, the main drag and beach front remains endearingly ugly to us locals in the anarchic way of many highly-populated beach fronts along the Australian coastline. There’s graffiti along the beach wall, a raw-looking cement skate-boarding bowl and no matter how hard the local council tries to renovate the parkland above the beach by continually erecting and dismantling semi-permanent scaffolding and replanting the turf, it stubbornly remains patchy and threadbare.

Purists decry the eyesore car park right along the beach front whereas we locals rather like the easy access it gives us to the beach, the surf clubs and the outdoor gym.

You see that’s what Bondi has always been about. Easy access over trendiness. Egalitarianism over elitism. People taste over designer perfection.

I understand that the heaving weekend crowds in summer can be off-putting for those looking for a quiet flake and bake but the miracle is that so many bodies - fat and thin, young and old, designer and frump, wealthy and poor, tight and collapsing - can gather together to do something as frivolous and pointless as slump on a wide expanse of sand and fall into water as clear as the sky above.

Sure, the horizon is a tad murky especially when the air pollution ratchets up in the summer humidity but a murky horizon comes with the territory. Try central Australia if you want a razor-sharp horizon.

The big

Bondi surprise is that most of the year the beach isn’t crowded. In winter it’s

often almost deserted. Sydney’s winter days tend to be clear and sunny, the

winter water temp a pleasant 18-20°C with a water clarity of sheer glass.

Long-neck cranes dive for fish, whales cruise by, pods of cartwheeling dolphins drop in,

occasionally a penguin arrives.

But whatever the season, most days of every week there’s space and peace for me to find the deep calm that follows an energetic tussle to get out through the waves, a point-to-point swim out back with only fish and seabirds for company, the frisson of sweeping in on a fast-running current dodging the sharp juts and jabs of the rock shelf on the way in.

Probably because it’s so well-known and such a drawcard for backpackers, Bondi has a reputation of being a beach for the rich and famous, the young, the bold and the sculptured. That if you’re, say, old or fat or frumpy, covered up or just plain ordinary, Bondi’s not for you. That you’ll feel self-conscious and out of place.

Following a whirlwind visit gathering evidence of Sydney’s raging affluenza virus for his book, Affluenza, Vermilion 2007, British pyscho-pyschologist, Oliver James, decided that Bondi had an ‘aggressive’ vibe. A kind of fuck you, we’re rich type thing, he explained to interviewing journalists. There was, he said, a beach culture of the body which must be hard on women.

If he’d made even the slightest effort to look further than the pre-determined stereotype he needed for his book he might have noticed men, women and children of every shape, size and ability, colour and nationality walking and running up and down the beach, swimming, riding boards, playing games, skate-boarding or just hanging out.

What a shame he didn’t stop long enough to have a yarn with some of the oldies at the surf clubs; men and women in faded swimmers who have rarely missed a daily swim for forty years.

And, I’d be pretty sure he missed the mysterious Bondi eruv, a thin wire high above the people, the sand and the sea, stretched from slender pole to slender pole. An elusive minimal wall that extends the boundaries of the home to the neighbourhood and allows observant Jews to stroll along the beach front on the Sabbath carrying their possessions and their children.

It seems to me that the pyscho-psychologist got no further than the outdoor gym where the muscle-bound strut their stuff. I’ve always found them humorous rather than aggressive and must own up to eyeing off the beautiful bodies performing their clever feats as I wander by.

By carelessness or choice James never saw Bondi’s beauty, freedom and eccentricity so engagingly captured by Dorothy Hewitt in Bobbin Up, her famous novel set in the 1940s working-class Sydney:

The sun sank in a blood-red ball balanced on the roof of the city. They smelt the tang of the sea, drowning in the stink of asphalt, hot tar, exhaust and sweat. It was Bondi, a great, dark, silken, heaving surf in the heart of Sydney. They followed the crowds, streaming off the trams and buses, laughing, moving inexorably, patiently, thankfully, towards the thump of breakers, the moonlit curl of white on the sand

Hand in hand Ken and Dawnie picked their way delicately between the sprawled bodies, old and young, fat and thin, rich and poor, all shapes and sizes huddled under the deep blue roof of the starry sky. Bondi in a heat wave was a great leveller.

Bobbin Up, Dorothy Hewitt, 1959

In his eagerness to find misery rather than joy James also failed to notice – or ignored - the abundance of laughing, smiling faces as celebrated by the ever-observant Helen Garner:

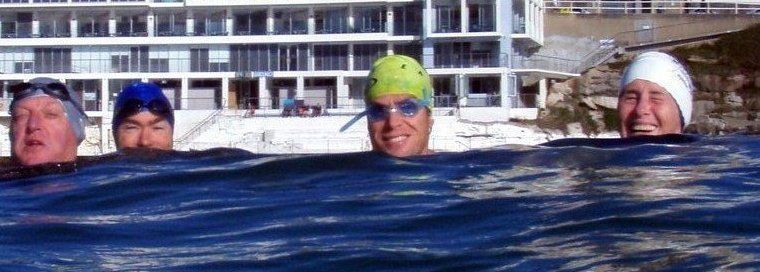

Swam early at Bondi with Sally and Patrick. Crystalline waves toppled. We stood up to our chins in water of palest, glassiest green and grinned at each other, speechless. A boy of the awkward age – thirteen – shot past us on a boogie board with a look of shameless ecstasy on his face.

Helen Garner, The Feel of Steel, Picador, 2001

*

Robin Barker: Baby Love, The Mighty Toddler, Close To Home