The Activity Trap

- By Robin Barker

- •

- 15 Feb, 2017

I’ve always liked the idea of teaching kids to read and swim as soon as possible. Apart from any other considerations – fun, pleasure, pride in self-sufficiency, - once children can read and swim life for their parents becomes much easier.

Thus, when I became a grandmother I decided to take responsibility for my grandchildren’s swimming. Not just lessons but how to have fun in the water as well.

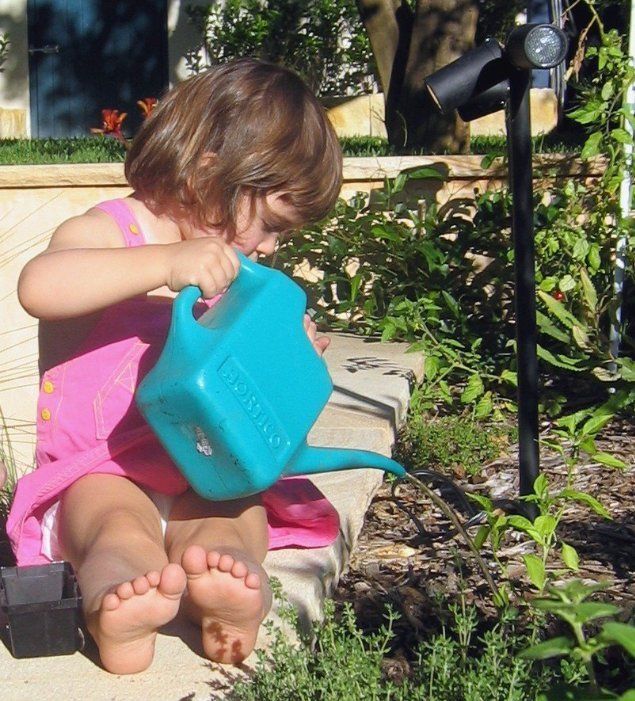

When Sage was a toddler we spent

Friday mornings at the Boy Charlton Pool where we frolicked in the water under

big shade cloths. Sometimes we were frogs, ribick, ribick, ribick, hopping slowly along the

steps, sometimes we were dolphins leaping up and down, and sometimes we made a

shopping list and swam to the fish supermarket located at the far end of the pool.

At intervals, we sat on the warm timber deck and ate chunks of watermelon and

squinted across the harbour at the boats.

Sage’s water skills improved over the summer until she was able to keep afloat by treading water. But as her body was still vertical I decided we’d join the swimming classes held at the pool in the mornings where I’d noticed babies and toddlers having lots of fun bouncing around with their mothers guided by the teacher, a kindly, energetic woman who gave everyone massive amounts of individual attention. Perfect.

I signed us up for a term. Secretly I thought I was a groovy granny. I had visions of telling my granny friends how I taught my granddaughter to swim.

Sage looked dubious on the morning of the first lesson but I ignored it. I knew she was going to love it.

She hated it.

Not because anyone was being mean or because she was being forced to put her head under or to do anything scary. She was puzzled because our play time had suddenly turned into a classroom. As I struggled to make her join hands around the magic carpet and ride the noodle she kept pushing away.

‘Why can’t we go and play Grandma?’

My composure wobbled. The other toddlers were doing it. Why wouldn’t Sage?

‘I want to go to the fish supermarket.’

‘Sage I’d like you to join in…here we go…round and round the mulberry bush’

‘I want to be a dolphin’

‘Sage please sit on the noodle like the others.’

‘I want to get out.’

To my horror, I felt a knot of exasperation in my tummy. Lips thinning, I told the teacher we were leaving the class.

‘Are you sure?’ she said. ‘Sometimes it takes a while for them to get used to the structure.’

‘Grandma, I want to get out.’

I was aware of sympathetic eyes upon me. I closed my eyes, counted to ten and together we left the pool. I stared out at the harbour while Sage got stuck into the watermelon then, pointing her bum to the sky, peered through the cracks of the deck at the water below.

‘Now can we go and play?’

I laughed. My tummy knot dissolved. If it’s so easy for a grandma to fall into the activity trap what hope is there for parents? Somehow, I’d managed to turn fun with granny into ‘it’s time you learnt to swim whether you want to or not’ without stopping to consider whether that’s what Sage would prefer on our Fridays together. It was important that she learned to swim but it didn’t have to be with me, right then.

*

Few of us are immune from the compulsive necessity to stimulate our children’s natural development by enriching their environments and keeping them fully occupied with a smorgasbord of structured activities.

Increasingly parents feel obliged to saturate their children with all manner of enriching activities to ‘give them an edge’, ‘make sure they are not missing out’, ‘keep them out of mischief’ and ‘help them fulfil their potential’.

And with, perhaps, the deep-down secret hope that they might roll out at the other end as lawyers or doctors, world-class musicians, award winning actors, celebrity chefs or very fast swimmers.

Why the pressure?

Finding hard evidence to work out why modern parents are so driven to provide their children with more than their children need or more importantly, can happily accommodate, is difficult.

Some possible reasons:

- Increased affluence has made it possible for many of us to give our kids all the opportunities we wish we’d had – horse riding, the cello, drama classes, pottery and Spanish.

- Perhaps at times guilt – compensation for marriage bust-ups or both parents working long hours to stay on top of the mortgage and the school fees.

- The pursuit of academic excellence for their

children is epidemic among middle class parents. They feel pressured to make

‘sacrifices’ and to work long hours and go into debt to give their children

what is viewed as the ‘best’ education.

‘Best’ is often measured by social status, exam results and university entrance stats.

If the local comprehensive high school is perceived as being a dump - as these days it so often is - the rush to expensive private schools is understandable. The fact that most politicians' kids go to private schools, is not a great advertisement for state school education.

- The blame for this general trend cannot be laid solely at the feet of ‘pushy’ parents. Right from birth, even prior to birth, parents are urged by all manner of experts to provide their babies with ‘optimum developmental’ activities to foster higher IQs, enhance fine and gross motor skills, and to generally get babies and toddlers to achieve as much as possible as quickly as possible.

- Brain research is flourishing. A torrent of books, articles and media reporting alert parents to the necessity of adequate stimulation to the baby brain. A common theme that ‘it’s all over after the first three years’ implies that if an opportunity is missed the baby's future is irredeemably compromised.

- The explosion of research into human development has led to a huge commercial child development industry which many parents find irresistible. Most of these ventures, marketed under a guise of breakthrough science, are profit driven rather than by what is necessary or even helpful for normally developing children in good homes

- We live in a highly competitive society and it takes confidence and strength not to get caught up in the child-rearing competitiveness that has always been around but seems to be more intense today than ever before.

*

Putting it into perspective

Extra activities can be fun, rich and interesting. Occasionally a childhood activity does lead to an absorbing lifelong vocation. But generally, activities should be viewed as the icing on the cake, not the cake.

Bear in mind:

- If you expect too much too soon you might be unintentionally setting your child up to fail. It’s very helpful to understand normal child behaviour and development before launching your child into a host of activities he may not be ready for.

- Try to ignore the ‘first three year’ mantra. Doors never close. Children can benefit from exposure to complex, enriched environments throughout their lives. Earlier is better is only because enrichment that starts earlier can potentially (if the interest is sustained) last longer.

- Make sure there’s time every week for unstructured activities – messing about time, which includes getting bored time so children can learn how to use their own imagination and resources to entertain themselves (no, I'm not talking about drawing on walls, spreading Vaseline around the bathroom, cutting hair or experimenting with make-up - obviously, depending on the age, some supervision is required).

- Make sure the activities do not overextend you

financially, physically or emotionally.

Financial stress eats into the fabric of family life. And the unrelenting pressure of rushing kilometres morning and night for a myriad of activities can rob family life of the nice bits – the cosiness, the laughter and fun, the mad silly moments – because everyone is so irritated and exhausted.

When to call it quits

Knowing when to let go is an art and I hesitate to make suggestions as it is such an individual decision.Most of us know someone who claims they would never be where they are today – world’s best swimmer, violinist or scientist – if their parents hadn’t pushed at some stage.

On the other hand, the world is full of people who spent significant childhood hours half-heartedly doing activities they had little or no real interest in wasting their time and their parents’ money.

In the end, it’s up to your child. Constant nagging to practice and urging to her to get to wherever she is supposed to be on time is perhaps a signal for the end of the activity.

*

Book Shelf

Walker Kathy, What’s the Hurry? Reclaiming childhood in an over-scheduled world,

Australian

Scholarships Group, Australia, 2005.

http://www.earlylife.com.au

Bruer John T, The Myth of the First Three Years: A new understanding of early brain

development and lifelong learning,

Free Press, USA, 2002.

http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/parentingculturestudies/files/2011/09/Special-briefing-on-The-Myth.pdf

*

Robin Barker: Baby Love, The Mighty Toddler, Close To Home